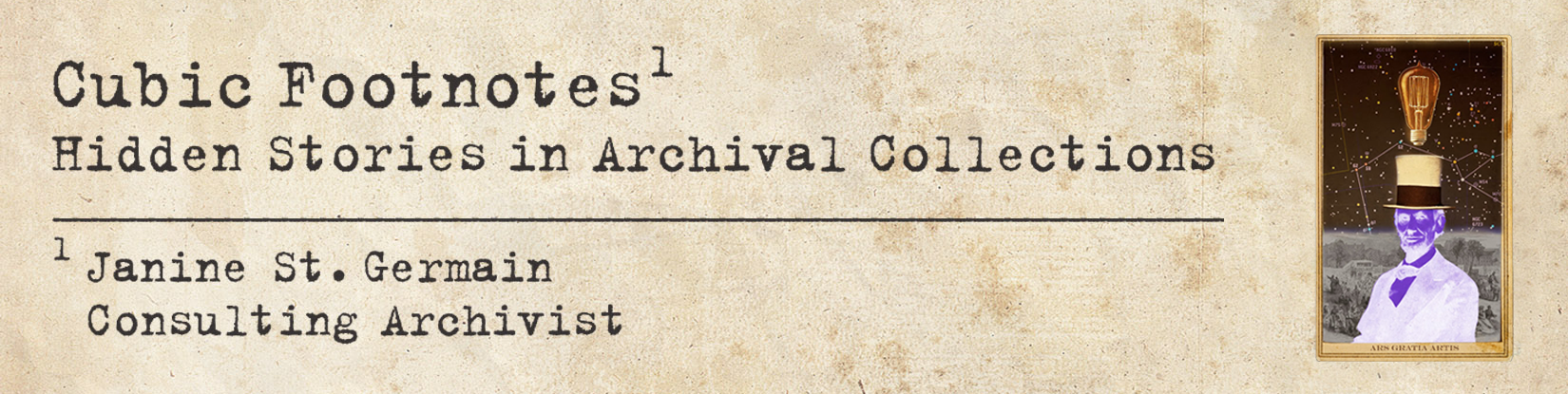

A CONVERSATION with the Brooklyn Museum’s Manager of Digital Collections & Services, Deb Wythe: The Analog and Digital Life of the Brooklyn Museum Archives

Deb Wythe is a friend and colleague whose friendship I have valued for many years. When I first took the leap into becoming an archivist in Prospect Park a long while ago, Deb was one of the first professionals in the field who provided guidance and enthusiasm right from the start. Brooklyn Museum is one the Park’s cultural neighbors, and I was so grateful to have found an archivist friend so close by.

COLLECTION: Records of the Office of the Director (W.H. Fox, 1913-33)

LOCATION OF COLLECTION: Brooklyn Museum, Brooklyn, NY

Janine St. Germain: Deb, what has stuck in your mind all these years, when pondering the institutional records you worked with in the Brooklyn Museum Archives?

One of the things that has always fascinated me [about the archives] is how you can sort out personal histories, social histories and how the world the world at large has changed through studying institutional records. One of the themes that was always with me as I was working with the records of the Brooklyn Museum was the role of women in museums. Surprisingly, in the early 20th century—say the teens through the ’30s—women were a pretty powerful force in museum administrations. Not ours, not the Brooklyn Museum, at that time — our first director was William Henry Fox from 1913 through ’33, but he corresponded with a bunch of these women who were founding and directing museums.

This resonates with me right now because our new museum director is Anne Pasternak from Creative Time. We finally have a woman director!

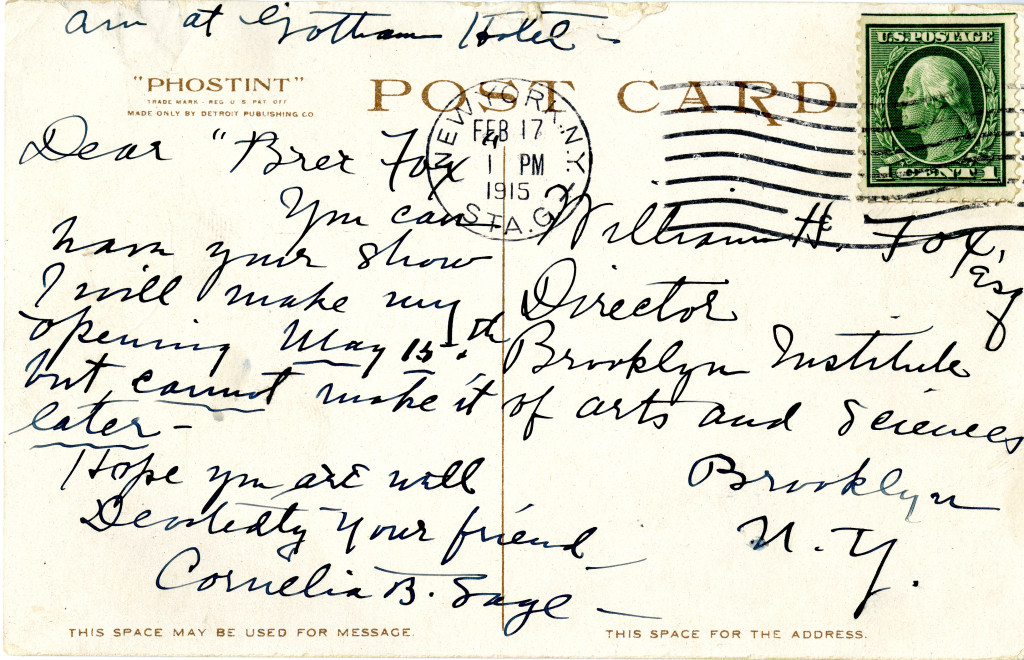

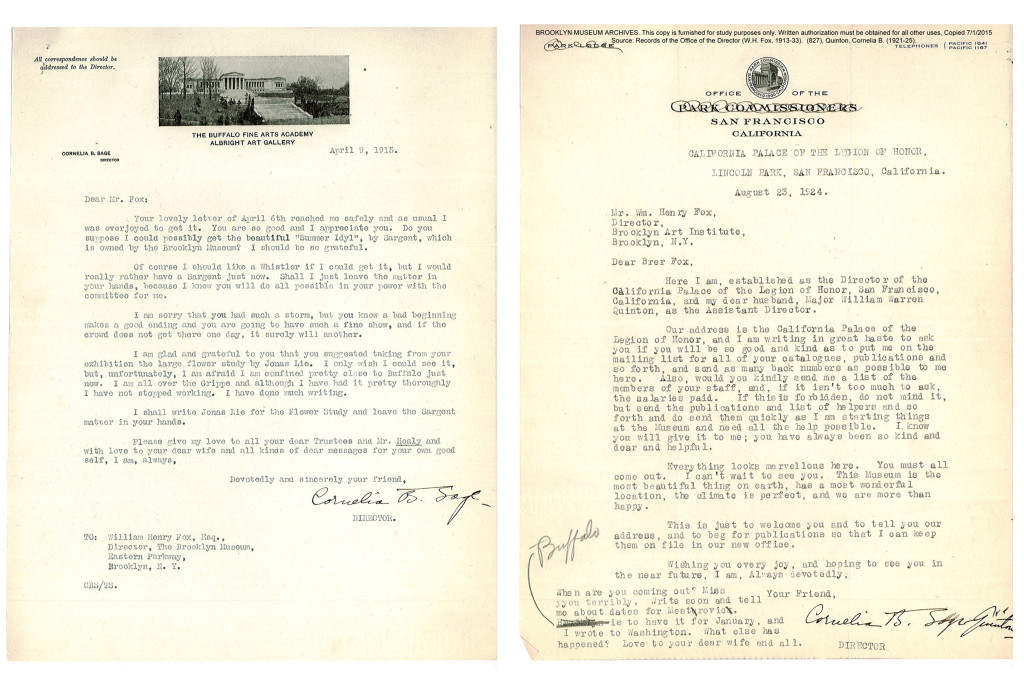

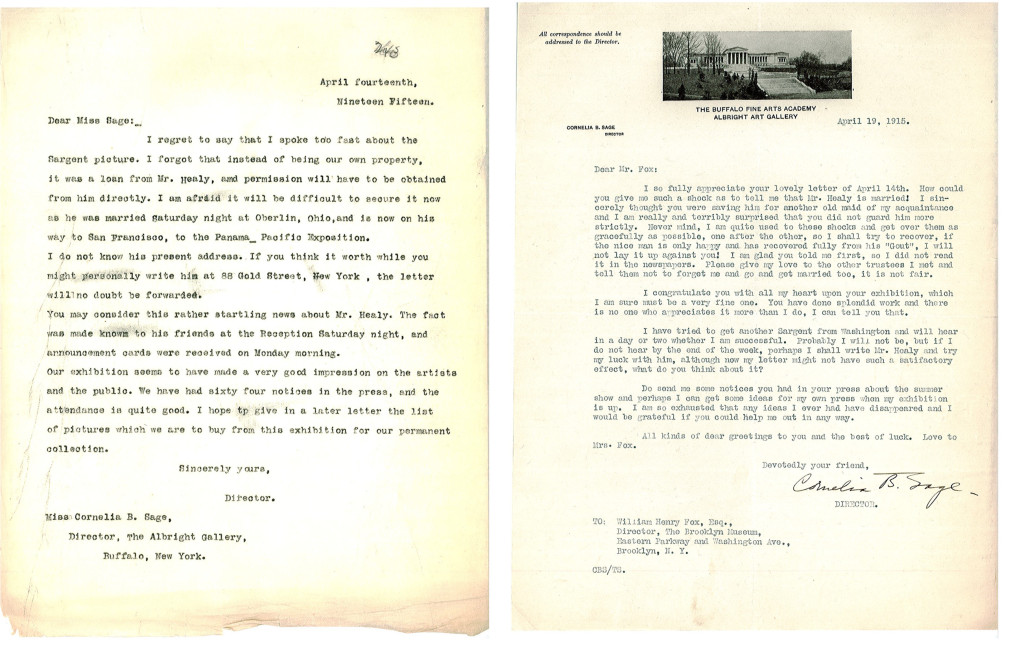

In the museum archives, there are two women who are featured prominently in Mr. Fox’s correspondence. One is Cornelia Sage Quinton. “Miss Sage” was director of the Albright Knox gallery, and then later, as Cornelia Sage Quinton (after she married Billy Quinton), she was director of the California Palace of the Legion of Honor.

They clearly had both a professional relationship and a very friendly, cordial, personal/professional relationship, sort of like many of us do as archivists. Cornelia addresses Mr. Fox in some letters as, “Dear Br’er Fox.” There’s also a formality. She signs her letters—she doesn’t sign them Cornelia—she signs them with her full name. Sometimes she addresses him as Dear Mr. Fox, or Dear Dr. Fox. He always addresses her as Miss Sage, or Mrs. Sage Quinton later on.

Another collaboration that, I think, was pretty intense was with Beatrice Winser, the director at the Newark Museum. They both were training apprentices–including women–in museum work. These apprentices went back and forth. They would come to the Brooklyn Museum and then meet back in Newark. The upper administration was really concerned about building up a museum profession…. People came into it from art history, business, education and family connections. I just found that whole area very interesting.

JSTG: I’ve been thinking about forms of correspondence and the shape it takes now in the digital world. I’m beginning to think that the subtext of these conversations that I’m having with colleagues is about this changing form of communication and the sharing of ideas.

I do think [correspondence] is still happening. It’s just that we’re having trouble capturing it. A lot of the [analog] letters held in the archives were not long, thoughtful letters. They were almost like emails. They’re a paragraph, or five lines. I think that the business of people’s lives happens within the letters. I think they used to get two or three deliveries a day of letters. You would send a letter and a person would get it the same day, or the next day if they were in another city. In a way, the letters and telegraphs are very much like email.

Of course, I think we really lost some of that when the telephone came in. You and I have our deep conversations in person or over the telephone because we have that option, whereas in the 20s…I think the museum had one telephone. I’m not sure when every office got a telephone. You start out with conversations, and then you go to letters. Some of them are long and really helpful and really personal and deep, but a lot of it is everyday business. There were telegrams … and then telephone and then, now, email.

JSTG: Do you feel like, with email, there is a depth of content that is harder to draw from…compared to the content in these analog collections of correspondence?

I think so. The problem is capturing it and organizing it. Back in the day, there were secretaries who typed and checked the copies and filed them in ways that archivists can now pretty easily process them and make them accessible to people. You have a folder of all the correspondence with a particular person and you can read both sides of the exchange.

Then, there was this whole period in the ’80s, ’90s where, at least in my institution, they no longer had professional secretaries, so filing went to hell. It was even harder to find stuff. Now, everybody keeps their own emails in their own email inboxes and it’s totally unorganized, mostly. We haven’t yet figured out the best way to capture emails and provide access to them. I think that’s a big mystery. How are we going to make sure we get them and make a way for people to read through them and find the stuff they want and not have to read through the same thread….

JSTG: Deb, how did the museum archives initially get assembled?

When I started at the Brooklyn museum in 1986, I was there on a National Historic Publications and Records Commission grant. There was no formal archivist (until they got that grant), so my job was to find all the records that were scattered around the building and stored everywhere—from offices to basements to crawl spaces. There was a space under the dome where, over the years, people had just stashed away boxes and filing cabinets. It was a challenge to bring all of this stuff together. It took several years before we actually found all of the directors’ files. When I first arrived there, those first 20 years of director’s files had been rescued by the museum registrar and were in her office. She was looking into documenting the collection.

JSTG: So, thanks to the registrar—another female, I should add— that part of the archives of the Brooklyn Museum became a reality. How did you then prioritize which pieces you would start processing first as you found them? Were you doing it alone?

In the beginning, I was pretty much a lone arranger [as a member of the library staff]. When I was first there I had a part time assistant who did some processing and some data entry. For the most part, I did the processing and wrote folder descriptions and the assistant put them in a little database on our standalone computer.

The first few years, I did a lot of processing, but as an institutional archivist, you’re also trying to build up your institutional credibility and usefulness. I made sure that everybody knew what we had and I did reference for people, especially for those on museum staff, but also for people who found us from outside. Every year, the reference pretty much doubled. 75 reference requests in the first six months. Then it was 150. Then it was 250. Pretty soon, you had no time to process because the whole purpose of an institutional archives is to be useful to the institution.

JSTG: What has it been like to weave the analog world at the museum with your work now—now that you are completely dedicated to digital preservation?

The transfer to digital started to happen around 2000 because we were starting to do so much digitization in the museum archives, using soft money and putting the results up on the website project by project, which was not easily sustainable. We were managing them in homegrown Access databases, not the actual images, but the metadata. At a certain point, you hit a critical mass when you really shouldn’t be doing that any more. We had 8,000 images. Then, suddenly, it’s like, “We’ve got to make these more easily accessible so people can see them.”

I reached out to people in other departments around the museum in 2004 because, as an archivist, I had my tentacles everywhere already. I said, “Let’s see if we can get together and get the museum to buy a digital asset management system that we could all share.” Somebody in administration saw what we were doing and said, “Yes. We need a centralized imaging department. Would you organize it?”

JSTG: How did you capture all that information? Were you creating spreadsheets and bringing all that information back to your office?

I talked to people and took notes. I had a survey form that I filled out. I crunched the data into an executive summary, which I gave to the administrators. They said, “All right. This is what we’ve got, this is what we’re going to do, and this is why.” My charge in starting the digital lab in 2005 was to create a new department with no extra money and no extra people—typical for a non-profit institution.

I moved into the photo studio. I brought along myself and a half-time person from archives. The person doing rights and reproductions came over from merchandising. I was able to cobble together a digital imaging archivist position using some education funds with people that had used the acquired images for education programs and over the years, have managed to morph that little group of positions into two photographers, a licensing out person who does licensing reproductions, a licensing in person who does picture research for catalogs and exhibitions, a digital imaging archivist who does asset management, scanning, that sort of thing, and myself. I’m the manager and the database nerd.

JSTG: So, your role morphed from the earliest days of amassing all of that analog material, and now you’re working with image creators, re-creating digital visual material…

Right, and we’re very heavily involved with collection imaging. I would say 80% of our work is either photographing or scanning images of works of art in the collection. Another chunk of it is documenting the exhibitions. Then, we work with library and archives to do scanning projects. We do the scanning for things that the library needs or the archives needs. If they get a grant to do scanning, it’s generally done in the digital lab under our supervision.… We work with content curators and archivists to convert into digital and make it accessible.

The thing that I think I’m most proud of, besides making sense of all of this, is that it’s now readily accessible to everybody in the museum and, via the digital asset management system on the website, with a very quick turn around.

JSTG: I’ve got to ask, on the personal end, how do you not feel overwhelmed by all of this? How does Deb go to sleep?

The image that I like to use is this: it’s a mountain. There’s a bird that pecks away at the mountain. If you just keep pecking away, eventually you start to make the mountain smaller. I think archivists know that. They see a storeroom full of boxes. They just know they’ve got to have a plan and they’ve got to start with a box. We all have our things that we know are on the back burner. We say, “Okay, priority one: objects in the collection, priority two: exhibition images, priority three: libraries and archives…

JSTG: Is there anything that you ever miss from your pre-digital days now at the museum?

Oh, sure. I miss playing with analog stuff, with stuff you can hold in your hands. Doing research for this interview was really fun, just sifting through some folders and looking at the correspondence and getting back into these people’s lives. There’s a joy in that. My job now is a lot of data crunching; I do a lot of image loading, I do a lot of management, which is really easy with my current group of people.

JSTG: Here’s a question, Deb. Tell me if you have experienced this or not. When I open that first box that’s completely raw, it’s almost as if you hear the voices of all these family members competing. There’s a whole cast of characters that you immediately recognize and feel affinity for, certainly more so as you get through the collection and work with these characters—such as Mr. Fox and others. I’m wondering how parts of that may or may not translate into raw digital files as you start.

Most of the work I do now is with images of works of art. If there are people in there, it’s the artists, but they’re one step removed. I do find I get to look at a lot of art and a lot of objects that you wouldn’t necessarily see in the galleries. There’s a textile inventory now, and images of textiles are coming through– thousands of textile swatches. There’s something rewarding about seeing them in their huge groupings. You get a sense of what it is. It gives you a grasp of the whole museum’s collection and that’s rewarding.

JSTG: Any final thoughts, Deb?

I think that there have been two things that have kept my career interesting. One is that there’s been something new about every five years, to keep me engaged and interested. I think that’s probably the ideal. It didn’t always happen, but in the last 15 years it has. That has kept me fresh. Finding new hats to wear is really valuable. The other thing is professional involvement. Being involved outside of my job, and outside of my institution, has kept my interest alive and has kept me learning. I have professional connections in museum archives and in museum technology and in copyright and in imaging.

Within each new area that I’ve gotten involved with, I’ve found a new community and new people to learn from and to talk to—and to share with. I think that’s super important. With my interns, I always suggest joining Archivists Round Table. Join the Society of American Archivists. Join the Museum Computer Network. All these things will make your working life more interesting.”

==========================

All images provided by the Brooklyn Museum Archives.

Source: Records of the Office of the Director (W.H. Fox, 1913-33), Paintings (1913-33).

==========================

Edited and condensed for clarity.

Janine St.Germain is a Consulting Archivist. To learn more about her work, visit janinestgermain.com

Hi Janine,

I enjoyed this very much. It brought back memories. When I was in grad school (1979-82?) I worked at the Brooklyn Museum, first in African, Oceanic and New World Cultures and then for Michael Botwinick the Director for a year, then back to AONWC. I spent a lot of time cataloguing uncatalogued material, mainly Oceanic textiles. I kept finding treasures throughout the museum. One day I found all of the Culin Diaries tucked away in the library and set up shelves for them in the office of AONWC. Totally amazing dairies from the first curator of Primitive Art at the Brooklyn Museum. It was not only a complete record of all of his acquisitions but writings about the indigenous people accompanied by gorgeous photos. My favorite correspondence I found in an old file cabinet was a letter from Hellen Keller. I hope you friend Deb Wythe had a chance to see the Culin Dairies in the AONWC department.

Best,

Ellen

Yes, indeed, we did bring the Culin expedition reports into the archives. What a treasure.

And I also remember the Helen Keller letter, which was in a folder titled “letters from notables,” along with one letter each from Albert Einstein and Charles Lindbergh. We were never able to figure out where in the collection they had originally come from — the classic archives dilemma of loss of context when there’s no “original order” to help you make sense of things.

DW