New-York Historical Society, Sigmund and Margaret Nestor Papers, 1942-1945

CONVERSATION WITH ARCHIVIST CELIA HARTMANN

Discussing the understated and extraordinary value of hand-delivered correspondence

Celia Hartmann is Project Archivist for a variety of institutions, including collections held at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Museum of Modern Art and the New-York Historical Society.

COLLECTION: Guide to the Sigmund and Margaret Nestor Papers, 1942-1945. The collection includes correspondence between Sigmund Nestor, from U.S. Army domestic camps in 1942 and 1945, and from India and China in 1945 and 1946, and his wife Margaret Nestor in the Bronx (1942) and Florida (1945-1946). Included are letters, postcards, and a telegram; enclosures from the letters; and the Nestors’ wedding announcement.

LOCATION OF COLLECTION: New-York Historical Society

Part of NYHS’s mission is to document and interpret the cultural history of New York City and the state of New York.

Finding Aid

===================================

Janine St. Germain: So Celia, tell me about this collection. Why has it lingered in your mind?

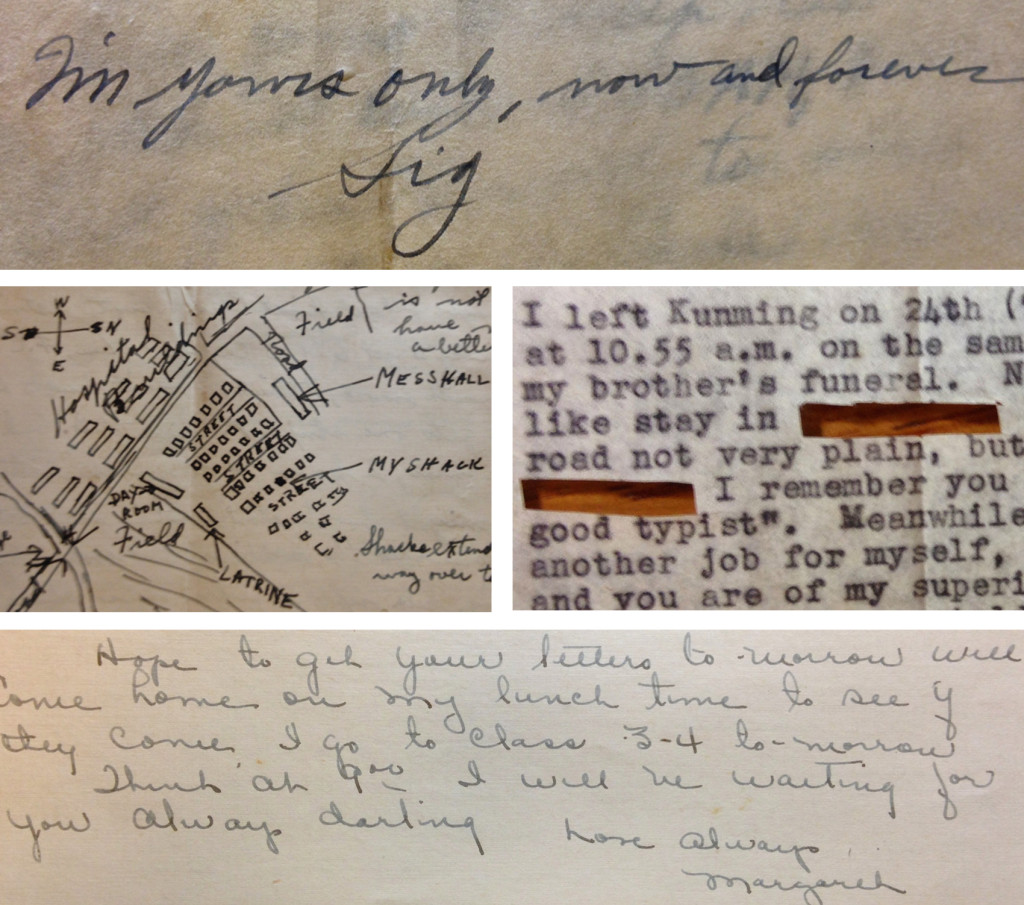

Celia Hartmann: First of all, it was the first collection that I ever processed. I worked on this collection during my internship in library school. It was the first time that I was applying theories I had learned to an actual box of material. It was something that nobody had looked at or done anything to since the collection was purchased. I was presented with bundles of letters, all tied up with ribbon.

JSTG: How large is the collection?

It’s five document boxes. Not even two linear feet. The collection is comprised of correspondence between a young man who volunteered, I think, for the US Army in 1942. Sigmund did basic training in New Jersey, and was in a training camp on the West Coast. Then he was in India and in China until he was demobilized after the war.

He had just gotten married. I think he was 18 or 19 years old. He was really young, and he was a train mechanic on the subway. He lived in the Bronx, probably near Woodlawn, and his wife was training as a nurse. The story was this amazing personal story of what it meant to serve during that period, because they were very young, very much in love. They missed each other desperately, and from the letters, it became apparent that he had perhaps left her with some “equipment” that would keep her from missing him so much.

When he got to China, I think that was his final posting. He worked in the commissary on a big base. He filled out forms to make sure there were enough chairs for the lecture halls … nothing to do with warfare, but a lot to do with administration.

He was taking all these courses, which he could do as part of the military. Margaret couldn’t afford to live in New York in their apartment anymore. She moved to Florida where her mother was living, and she lived with her mother. The couple made plans to buy land and start a farm. He was taking carpentry and business management classes, and the letters were full of promises, such as, “When I get back, you’re not going to have to work anymore. We’re going to have a family.” Here was a woman who had been a working woman, and an independent woman, and all she and her husband wanted was for her not to have to work and for them to have a family. In this tiny collection, you can clearly see the precursors of the baby boom entering their conversations and concerns: you can see the 1950s coming.

JSTG: It’s such a snapshot of that time.

It’s totally a snapshot, and these were really ordinary, uneducated individuals. They graduated from high school and then started to work. The collection contains complicated negotiations about when he would be demobilized. They were doing lots of math about how they were going to afford a new life together.

The other part that made an impression on me was that Sigmund had never been out of the Bronx, maybe he’d been to Coney Island, but here he was in Asia with colleagues who may have been more worldly, or thought they were more worldly than him. He also could get off his base pretty easily, it seemed. He starts to go to the local markets, and then discovers pornography, and starts making purchases. In the letters, Sigmund tells Margaret about these things, and towards the end when they’re getting to the nitty gritty of their planning, e.g. where he’s going to send his stuff and how much there is and and that the packages are numbered. He shares, “There’s six boxes but don’t open box four until I get there.”

JSTG: So, theoretically, she received those boxes, but they are not included in the collection?

No. But the collection holds both sets of the letters, his letters and her letters. There was very little visual material included in the collection. There were a few things he enclosed, some clippings and maybe a picture of him and his buddies. The collection includes their wedding picture, I think, or their wedding invitation, but I had to piece all this together from the materials themselves. The material had been stored pretty badly, there were many mouse nibbles which actually helped in figuring out which items went together, because of the mouse nibblings. They also had been pierced by the sensor. The sensor had applied a puncture marks on the correspondence. They probably wrote each other every day. Many letters crossed each other, and they have each one of them annotated, when they answered it. Really intense record keeping on their part.

JSTG: Over time, do you find this collection has somehow connected in your mind to other collections on which you have worked?

I’m not sure if it’s so much the content of the materials. In other collections, I’ve run into other war time materials that were very interesting in terms of how the war affected the correspondence. This kind of correspondence serves as a sort of artifact of what had happened. People sent letters to war zones, and they were actually delivered, which is incredible. They were in sacks, and they went on boats, and then, they got transferred to Jeeps or however the hell they got them. There was an importance that was given to communication … it is something that is also disappearing. This was a real fragment of these peoples’ lives.

Right now, I’m working on the papers of the man who was first paid Director of the Metropolitan. There is so much information about him. But in the case of the Nestors, this couple could be seen as a complete nonentity. The fact is, the collection is so small, yet it contains so much information.

JSTG: What do you feel might be overlooked in the value of this collection? Perhaps the importance of communication? Or the form in which the information traveled?

That is something I’ve been aware of through the collections that I’ve worked on. Brown Brothers Harriman (another collection processed by Celia Hartmann, also held at New York Historical Society — see the finding aid here), for instance, addresses the history of business communication from the late 18th Century into the mid 1960’s. One recognizes artifactual changes from those tissue paper copy books, to varying forms of duplication, to typing, and Thermofax. All of those issues, we take for granted now, as professionals. What I’m finding with the interns that I work with now is, many were born after 1990. That volume of paper correspondence is singular to them. I have a feeling that some of my interns have never put a stamp on an envelope and put it in the mail. In terms of the materialness, it is actually, perhaps, more precious for them.

Edited and condensed for clarity

Janine St. Germain is a consulting archivist. To learn more about her work, visit janinestgermain.com.

reminds me of how no story is too small to have impact and bring alive time and place and sentiment from another era. the pornography reference is an interesting tidbit that intrigues the reader to know more about this couple.

ah yes, i remember well the days of laboring over a handwritten letter (sometimes like newsy diary entries) and making my way to the post office so they would arrive as quickly as possible and then the excitement of receiving a reply in my mailbox, sometimes savoring the letter by waiting until the perfect time of day, with wine glass in hand, to rip it open and enjoy the correspondence (and these were not even love letters!!) Something gained, but definitely something lost in the immediacy of the digital age.

This is a very rich and rewarding discussion, with a lot of surprising and interesting detail. It’s gratifying to try to visualize the correspondence, too, even the paper they wrote on would reveal a lot of information. Congratulations on launching a great site.

wonderful interview. it is so full of understanding and empathy with the writers, not famous people, but real living human beings with profound issues and caring for one another. thank you.

Celia’s generosity in giving the limelight to a couple who would not have ‘made the headlines’ in their time or ours is really wonderful. What most people doesn’t realize is that these small family collections of correspondence actually contain gems like this that encapsulate the trials and successes of an era in a way that scholarly tracts never seem to do. Thank you so much for a great interview.