The itinerant archivist moves from repository to repository, ushering documents of note from states of jetsam/flotsam – often brimming from cardboard boxes once holding bottles of Smirnoff – into a state of order and meaning. Papers are shepherded into acid-free folders and boxes, where even the most cursory “To Do” list, meandering thought, or errant postcard suddenly, and finally, becomes — an objet.

I am continually inspired by this process.

I am inspired both by the physicality of handling the material and providing insight into its contents, as well as, and perhaps in particular, the chance to have yet another conversation with a being who completed an extraordinary life’s work. There is always a curious backstory lurking there, beyond the apparent reason why an individual’s papers are being preserved in perpetuity.

I recall Elizabeth Gilbert sharing that the poet Ruth Stone could feel a poem coming on “… like a thunderous train of air… it would come barreling down at her over the landscape.…”

I wouldn’t say I’ve ever felt a “thunderous train of air” when I crack open that first box of collected documents, but I do most definitely feel the aroma of a secret history that is about to be deciphered. This is an exhilarating feeling.

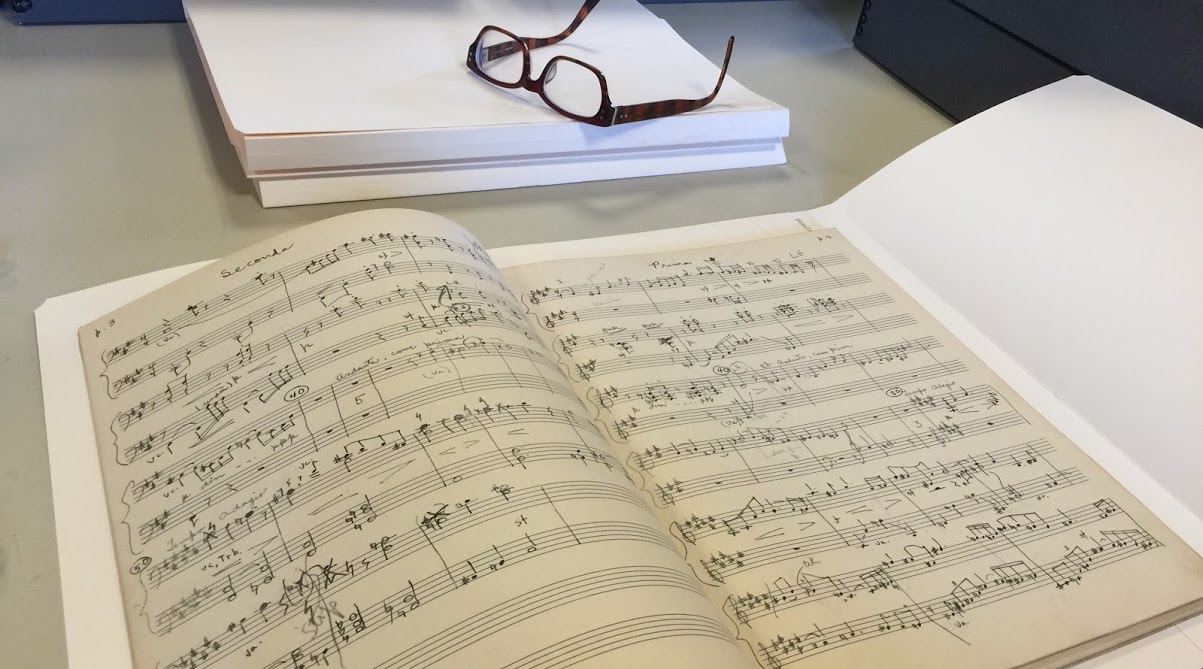

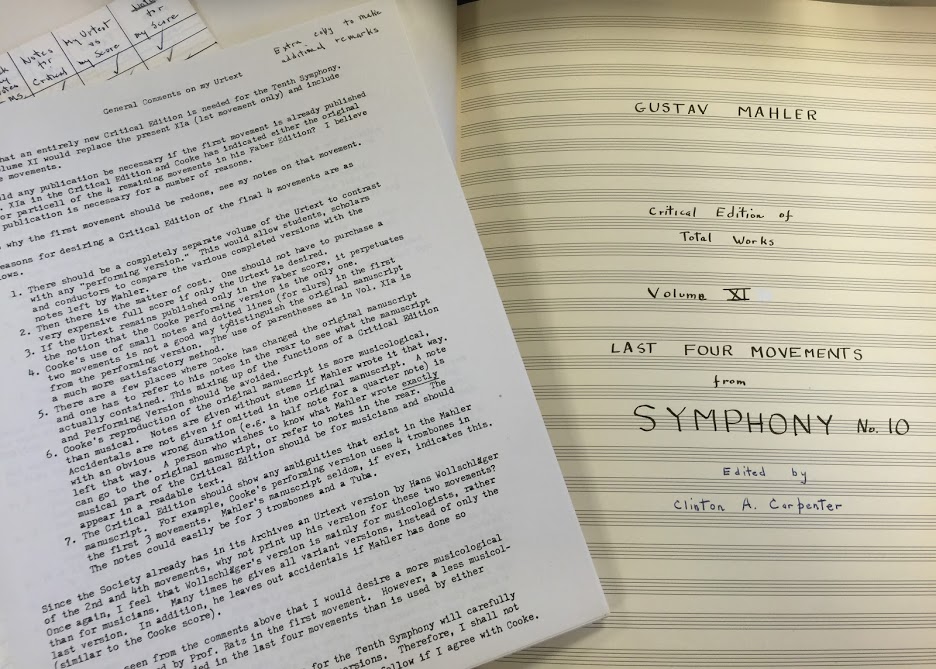

The backstory I am thinking about at the moment is the life of Clinton A. Carpenter. His papers have been left to Vassar College’s Archives and Special Collections Library. The collection is quite small, just eleven boxes. And the physical contents are really not that unusual: typed manuscripts, correspondence, musical scores, a scrapbook, press clippings….

Clinton Carpenter was a Chicago-based insurance underwriter born in 1921. He also worked in a retail music store in Chicago. The extraordinary element of Carpenter’s life was his unfailing drive to complete Gustav Mahler’s unfinished Tenth Symphony. Many of the notations in the collection are written or typed on the verso of various sheets of insurance company stationery. The mastheads include “Concordia Mutual Life – Serving Lutherans since 1909.”

I am humbled by the story of artists who have stuck with that day job. William Carlos Williams, Charles Ives and Wallace Stevens (curiously, the last two also worked in the insurance field). Carpenter, like these others, came home day after each long day and found respite working with abandon, responding to the muse that “barrels down the landscape.” Carpenter meticulously created notebooks documenting Mahler’s use of tempo and expressive terms. He studied Mahler’s handwriting, and compared Mahler’s works with contemporaries of his lifetime.

Carpenter, with a dogged drive for facts that I assume drew him into the field of insurance underwriting, was constantly searching for precise answers. Did Mahler ever use the bass clef for a bass clarinet? Did Mahler ever use such a tempo marking as Andante Allegretto? Did Mahler use horns in D? Carpenter persistently chipped away at all of this, I imagine, with every precious free moment at the end of each workday.

I love knowing that Carpenter lived to hear his own beloved rendering of Mahler’s Tenth. The Chicago Civic Orchestra performed his version in 1983. The Philharmonia Hungarica recorded it in 1994, and the Dallas Symphony Orchestra performed it in 2001.

Clinton A. Carpenter passed away in December, 2005. The rest of the story lies within the folders of the Papers of Clinton A. Carpenter at the Vassar College Archives in Poughkeepsie, NY.

_____________________________

As I processed Carpenter’s papers, I often listened to Gustav Mahler’s Symphony No. 10,” as realized by Clinton Carpenter – available on Youtube. Have a listen….

Also, see Mahler’s Unfinished Symphony, by William H. Youngren, The Atlantic, December 1998

Images: Papers of Clinton A. Carpenter, Archives and Special Collections Library, Vassar College

I see the fascination of letting realia concur up something of the inner life of a departed person. Since so much of a person’s own inner life is hidden even from the subject, I have to wonder what revelations might come of seeing, handling, reading the items that once played a role in our lives, things that we once made, used, loved.

I think the fascination is akin to the grip that fleeting apparently unconnected thoughts and feelings have on us as we explore grandparents’ attic or garage loft, or even finally pack up our own room back at our parents’ house. It’s personal archeology.

When it is a matter of things, they do speak but is it a wordless language, maybe more evocative than words. When it is a matter of words, well, even words tell a story and hide a story.

I think I get that you feel the the significance of the privilege and responsibility of methodically reviewing the remains, sometimes purposefully left, sometimes present by chance, of an inner life.

I think we can all feel the pull of an unsolved problem, but what of a problem that becomes a life work? But for what you said about Clinton Carpenter’s methods of research into Mahler’s patterns of behavior as a composer was very touching. Just to be able to do the research and understand the significance of his findings Carpenter had to be a real musician and then to be able to extrapolate from that and compose in the style of Mahler requires real talent. I have to wonder at the humility of Carpenter, who, though with the technical skill to compose on his own, devoted himself to finishing another mans’s work. Or was the devotion derived from some lack of faith in his own creativity. What do you think?

Tom, first of all thank you for a beyond stupendous question.

You know, I couldn’t say from working with his papers if he may have been uncertain of his own creative pulse. I can say however, that he was indeed devoted…as his documentation so clearly evokes an unwavering commitment to detail. Not only in his orderliness, but also in his own self analysis, as he attempts to interpret Mahler’s voice. It is fascinating to consider the attempt to pick up a thread where one has been left off. Beyond the style of fan fiction, which is popular today.

Yes, doing this work, as an archivist, is a privilege and responsibility- and, come to think of it, perhaps not unlike Carpenter : there is a tug to “finish” an individual’s life work, by clearly interpreting the evidence left behind. From both a thoroughly objective perspective, while at the same time reveling in the nature of this particular human spirit, which for some reason, I have had the fate of “knowing.”

Here’s to human nature – as we are one in some way, you, me, Carpenter and Mahler

Janine,

This is a beautifully written and powerfully moving epistle. Your passion for unraveling and organizing archives to reveal meaning and intention are extraordinary. How lucky for you (and all of us mundane folks) that you get to dig into these archives and then share them in a revelatory form.

It was a pleasure to meet you when you were working on Nancy Holt’s papers.

Warmly,

Diane Karp